“I have a chance to kill some Russians.” Interviews with foreign volunteers in Ukraine

by Lindsey Snell and Cory Popp

On February 27, Ukrainian President Zelensky announced the formation of the International Legion of Defense of Ukraine and invited foreign nationals to come to Ukraine and join the fight against Russia. Foreign nationals, many with no prior military experience or training, heeded Zelensky’s call and poured into Ukraine. Months of reports of heavy casualties among the undertrained and often underarmed International Legion volunteers followed.

On July 1, the International Legion issued a statement on their social media accounts:

“Going forward, media enquires and requests for interviews regarding the Legion and with legionnaires must go through the Legion’s Communications Director, “Mockingjay” on Signal or Telegram only. We also remind all journalists that interviews and any communication with legionnaires are only legitimate if they are approved by the Legion’s press office, and that legionnaires are under strict orders not to talk to the press.”

The true number of foreign volunteers fighting in Ukraine is unknown. In March, the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs claimed more than 20,000 came from 52 countries, but many of the volunteers who came have already left. The total number of volunteer groups, both officially registered with the Ukrainian Armed Forces and operating unofficially, is also unknown.

After contacting the International Legion’s spokesperson, we received an offer to interview four British, American, and French volunteers under supervision at their media center in Kharkiv. While we weren’t able to make the appointment, we managed to interview ten other foreign volunteers in Ukraine on the condition of anonymity for themselves and the volunteer groups to which they belong.

The names used in this article are aliases. Nearly all of the volunteers we spoke to said there were severe issues with training, supplies, and communication. They said there’d been little progress on the Ukrainian side, and that morale was low.

“When Zelensky asked volunteers to come, I felt I couldn’t sit in France and do nothing,” said Bastien, a French national who came to Ukraine in May. “But I have been on the frontlines for more than a month. My body is tired. My spirit is tired. I just need to breathe.” Bastien initially planned to join the International Legion, but after meeting with the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense in Lviv, he was instead placed into a battalion within the Ukrainian Army.

“I had four years’ experience serving in the French army,” Bastien said. “I was in Iraq. The Ukrainians were very interested in my experience, so they put me in a special forces battalion. I’m the only foreigner in my group.” Bastien signed an indefinite contract. “I’ll be here until the end of the war.”

Bastien has been in the Kharkiv area since shortly after he arrived, and said the frontline fighting has been frustrating. “There are maybe three Russian soldiers for every one Ukrainian soldier,” he said. “That plus the Russian artillery and cluster munitions have really slowed us down. We are basically just trying to hold our position.”

Tamaz, a Georgian volunteer with six years’ previous experience fighting in the Georgian Army, was also recruited directly into the one of the Ukrainian Army’s special forces units. Tamaz has been on the frontlines in the Kharkiv region for the last month. He bought his own body armor and helmet. “The armor finally came in the mail,” he said. “And now, I’ll be broke until I get paid again.”

Tamaz says the war wasn’t what he thought it would be. “I don’t want to die here,” he said. “I got a dog before I left Georgia, and I keep thinking about how badly I want to see her again.” Like Bastien, the French volunteer, Tamaz also signed an indefinite contract.

Fewer Foreigners on the Front

Bastien says few of the foreign volunteer groups are actually fighting on the frontlines. “I see foreign groups sometimes, but they’re never on the front. They’re more in the backlines,” he said.

“The foreigners were being used as meatshields in the beginning,” said Sam, a 23 year-old volunteer from the UK. Sam had no previous military experience before coming to Ukraine in late March. He wasn’t accepted by the International Legion when he applied to join. “I think by the time I came, they realized sending a bunch of guys with no military experience into battle against the Russians was a pretty shit idea,” he said.

Sam recently joined a different volunteer combat group unaffiliated with the International Legion. “I’ve been training, but I haven’t seen combat,” he said. “My group is ‘reassessing.’” Volunteers from five different organizations said similar things about their groups stepping back from active combat in recent weeks, often to the dismay of volunteers who came to Ukraine eager to fight against Russian soldiers.

“Very few units are willing to push the lines forward again,” said Shaun, a 30 year-old veteran of the Canadian Army who came to Ukraine in June. “Most are burned out or wiped out. Scared or tired. I’m with a unit of volunteers who are very eager to fight. We’re all chomping at the bit. But reigns are getting yanked hard by the Ukrainian troops not wanting to disturb things too much. I think it means the Ukrainian military is burning out. There has been a loss of momentum. What started as a rest and reset turned into a static line.”

Shaun came later than many volunteers and said he was warned about the lack of organization among the military and volunteer groups. “But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t mind-blowing when I got here and saw it myself,” he said. “Units that need anti-armor weapons don’t have them, while units that don’t need them do have them. The level of clusterfuck here is extreme.”

“I suppose it’s not the story people want to hear, but the gap between how the war is shown in the media and the reality of the place is kind of ridiculous,” said Sam, the 23 year-old volunteer from the UK. “The lack of training and organization…I was working in a hospital for a while, which was frustrating, because outside of shrapnel injuries, most of the injuries were related to friendly fire.”

“Probably more than half the injuries are friendly fire,” confirmed Steve, an American who has been volunteering as a military and medical trainer since February. Steve was appalled by the mishandling of military aid that has been donated to Ukraine. “I fought in the Middle East and Africa, and I’ve never seen this level of corruption.

“Steel plates [in lieu of armored plates capable of repelling gunfire] were being given to front line troops who had three days’ of training. They were sent out with one rifle between a few guys and given 120 rounds of ammunition. Their commander and I begged the upper command not to ship the guys out, especially with that gear, but they didn’t listen. I’ve trained over 2,000 Ukrainian soldiers, and I’d guess at least half are dead.”

Although donations of military hardware and civilian aid have poured in from Western governments and private aid organizations, all of the sources we interviewed in Ukraine said that a substantial portion of the aid is stolen. “Both civilian and military aid goes missing,” said Mike, a volunteer military trainer from the UK. “This country has a corruption issue that will inevitably affect the outcome of the war.

“Absolutely everything—Javelin missiles, other missiles, vehicles, rifles, ammunition, grenades—all of it has been stolen. And it’s happening on both sides of the border. Lots of it is stolen in Poland, but it absolutely happens when it reaches Ukraine, too.”

The corruption and aid theft affects Ukrainian soldiers exponentially more than foreign volunteers. Soldiers from every Ukrainian Army unit we spoke to reported that many men aren’t given body armor. Units are dealing with a lack of vehicles, weapons, and ammunition. “We’re better off than the Ukrainians, because we can supply most of our own stuff,” said Shaun, the Canadian volunteer. “We buy our own gas, our own rations. My group is purchasing our weapons from large volunteer group. That volunteer group, which is not from a Western country, stole the weapons that it’s selling to us and other groups from the military aid coming into Ukraine.”

The Georgian National Legion

The Georgian National Legion formed in 2014, when Georgian volunteers came to fight on the side of Ukraine in the Donbas War. They claim to have more than 1,000 volunteers, including a number of non-Georgian foreigners. The faction was better equipped militarily than any unit of the Ukrainian Army or volunteer group we spoke to.

When we visited the Georgian National Legion in Zaporizhia, we were told that our Ukrainian fixer and translator would have to drop us off at a neutral location in the city. Georgian National Legion militants would then transport us to their base. “We can’t have Ukrainians we don’t know here,” said their commander, Mamuka Mamulashvili. “They might leak our location to the Russians.”

Some of the Georgian National Legion volunteers were outfitted with SCAR rifles. Inside the base, they had a shelf of small drones, highly coveted for their ability to search for Russian positions for Ukrainian artillery units to target. We interviewed one of the Georgian National Legion’s officers as he tested a Autel drone outfitted with an attachment to drop 30mm grenade rounds. When asked why he decided to come to Ukraine, he stopped working for a moment and looked at the camera. “I can’t fight the Russians in Georgia, so I am fighting them here,” he said.

After looking at some of my journalistic work, the Georgian National Legion officer grew angry and suspicious. “You support the Armenians,” he accused.

“No, I just covered the war in Karabakh,” I said, referring to my coverage of the war Azerbaijan, with substantial support from Turkey, launched against the Armenians of Karabakh in 2020.

“No, you are supporting the Armenians,” he said. He began to argue that Azerbaijan’s territorial rights to the disputed enclave of Karabakh were absolute. The Georgian National Legion’s volunteer medic, an American veteran, sat next to us, looking confused and uncomfortable. Not wanting the situation to degrade further, we decided to leave the Georgian National Legion base. We were followed by one of their vehicles until we left the city of Zaporizhia.

The Ultranationalist and Neo-Nazi Presence

Though many in the West have been quick to dismiss the presence of neo-Nazi armed factions in Ukraine as Russian propaganda, the presence of these groups on the ground is undeniable. A number of Western volunteers have joined Ukrainian nationalist battalions, among them groups affiliated with the Right Sector, Azov, and Carpathian Sich.

“When I was around Kiev and we trained a far right Azov group. And there we saw lots of Swastikas and Nazi symbols,” said Steve, the American military and medical trainer. “I remember walking the formation and saying, ‘Was that a fucking SS logo?’ I had the translator tell the Azov guys they had to take the Nazi stuff off, but they wouldn’t. So I told the higher command, ‘We’ll have people coming and giving us aid, and the second they see those fucking symbols, they’ll be done. We won’t get anything else from them.’”

The Right Sector is a far-right wing ultranationalist political organization that was founded in 2013. “I’m with a volunteer battalion that fights alongside the Right Sector,” said Tim, a 33 year-old volunteer militant from Florida. “And here is what I know. The Right Sector openly rejects Nazism and racism. Incidentally, the word ‘Nazi’ has been so abjectly abused by liberals that I’ve started using it as a litmus test. Because according to them, anyone right of Noam Chomsky is a neo-Nazi.”

Since February 2022, the content on the Right Sector’s official website and social media accounts has been fairly benign. But earlier posts on the Right Sector’s Facebook page rally against immigrants in Ukraine, the LGBT community, and Muslims. On their official website, the Right Sector posted photos of a 2018 rally held jointly with Carpathian Sich in Uzhhorod. Supporters are shown carrying flags with Nazi insignia. “Ideas of uncompromising struggle burn in young eyes and emit adrenaline. Nationalists know the price of spilled Ukrainian blood better than anyone else,” the Right Sector wrote of the event.

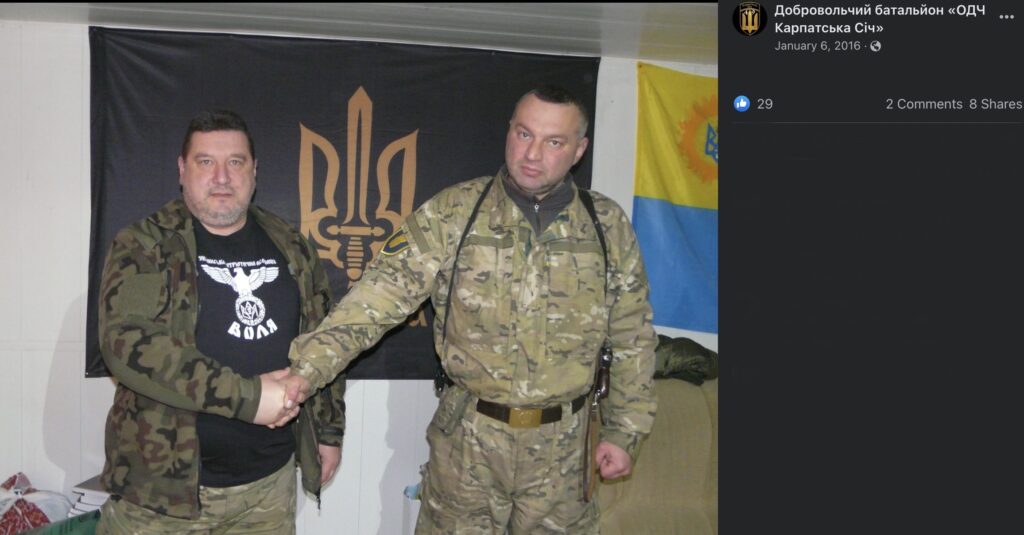

Carpathian Sich was established in 2014 by Oleg Kutsyn, founder of the Svoboda Legion, a military unit of Ukraine’s ultranationalist Svoboda Party. As of May, Carpathian Sich’s volunteer corps has been an official military unit under Ukraine’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. Kutsyn was killed in Izyum in June by Russian forces.

A number of foreign volunteers have joined Carpathian Sich. The group recently posted a memorial honoring Landes Sébastien Lionel André, Jacques, a 28 year-old French Carpathian Sich volunteer killed by Russian forces. French volunteer Bastien, a friend of Jacques’, says he doesn’t believe the group is racist. “There are minorities fighting in the battalion,” he said. When asked if they’d been aware of Carpathian Sich’s pre-war affinity for Nazi symbols, Bastien didn’t respond.

As with the Right Sector, the content posted by Carpathian Sich on their official Facebook account was markedly different prior to 2022. Nazi symbols are visible on uniforms, flags, and walls. In one photo from 2016, Oleg Kutsyn, the founder of Carpathian Sich, wears a t-shirt featuring a take on the Nazi Reichsadler.

“Yeah, it bothers me that there are neo-Nazis here,” said Shaun, the Canadian volunteer. “But it’s not in my face, so I just try not to think about it. And some of them are really good at wasting Russians.”

Shaun and the other volunteers we spoke to said they plan to stay in Ukraine until the end of the war. “I think the volunteers are making a difference,” Shaun said. “At least, some of us are. And war gives a new meaning to life. There’s a romance to it. When you see that much death and destruction, you sit and appreciate the beauty of the simple things in life. Also, I have a chance to kill some Russians.”

2 comments

Comments are closed.