“When I learned who Dylann Roof was, I began to admire him.”

Interviews with Ukrainian Ultranationalists

by Lindsey Snell and Cory Popp

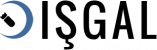

As Ukrainian forces took control of Kherson on Friday, soldiers flooded social media with victorious pictures and videos of themselves in the city. Nazi insignia was abundant, including Azov Regiment’s Nazi Wolfsangel, Totenkopfs, Black Suns, and patches advertising Misanthropic Division, a neo-Nazi organization that has recruited far-right volunteers for Azov from dozens of countries. As has become the norm, the overt displays of white supremacist ideology were unacknowledged in most of the major media coverage of Kherson.

“I agree with almost everything you’ve written about Ukraine,” said Mike*, a US military veteran and volunteer combatant in Ukraine, about a past article detailing mass corruption, theft of weapons and humanitarian aid, and inept military command leading to senseless injuries and deaths. “But I don’t believe that there are neo-Nazis in Ukraine. That’s just Russian propaganda.”

Steve*, an American volunteer military trainer, recalls seeing Azov Regiment militants covered in SS logos and Swastikas at a course he lead in Kiev. He asked Azov commanders to order the men to remove the Nazi insignia, and they refused. Still, Steve says he doesn’t think Azov men are truly white supremacists. “I think it’s just trendy to them,” he said.

Azov was founded in 2014 as a volunteer militia led by Andriy Biletsky during the Donbas War and was later integrated into Ukraine’s National Guard. Azov’s use of neo-Nazi iconography and abundance of members with far-right, white supremacist ideology immediately made them controversial, as did their violent attacks on feminists, minorities, and the LGBT community in Ukraine.

Major media outlets that condemned Ukraine’s ultranationalists in the years before the war now gloss over the history of human rights violations and white supremacist ideology of far-right organizations like Azov. In a piece examining Russia’s designation of Azov as a terrorist organization, German outlet Deutsche Welle writes, “the Azov Regiment originally grew out of a controversial right-wing extremist volunteer battalion. These days, Azov has been absorbed into Ukraine’s national guard, which answers to the interior ministry,” seemingly implying that the Ukrainian government’s legitimization of Azov eliminated the group’s deeply-rooted neo-Nazi ideology.

On a leadership level, Azov says it has purged its ranks of white supremacists. All of the Azov militants interviewed for this piece adamantly insist that they are not neo-Nazis. That said, all of the Azov militants interviewed for this piece openly display Nazi insignia and express white supremacist views.

Dmytro*, a 24 year-old Azov militant, posted a conversation he had with a man in Italy on his Instagram account. “Real Ukrainian warriors love their people and are proud that they are white Europeans,” he wrote. “Why does everyone cringe when they hear the word white?”

“I want my nation to survive and prosper,” Dmytro said in an interview. “I support traditional values and the revival of white Europe. It’s important for white families to restore the greatness of Europe. Look at America. It’s a crime to be white. Look at Black Lives Matter!”

Centuria

Dmytro joined Azov through Centuria, a far-right Azov spin-off organization led by Igor Mykhaylenko, an ex-Azov commander who has been referred to as Azov founder Andriy Biketskyi’s right hand. Mykhaylenko went on to lead the National Guards, the militia associated with the far-right National Corps party. In 2020, Centuria emerged as a rebrand of the National Guards.

Centuria began steadily supplying its members to Azov units after the start of the war in Ukraine. “Centuria basically became the backbone of Azov Special Forces,” Dmytro said. “We are very important to the war effort.”

Centuria describes itself as a group that, “stands on the ideological foundations of Ukrainian Statehood and European traditions.” Centuria members espouse white supremacy, misogyny, and homophobia. “Terrorism is the result of Western Europe’s multicultural policies,” Centuria wrote on its Telegram channel. “The only thing that can save France is the nationalists.”

Vitaly Avramenko, a commander of an Azov Centuria Special Forces unit, referred to the Zelensky Presidency as the “Jewish government” on his Telegram channel. Der III Weg, a German neo-Nazi party, celebrated the inception of Centuria on their website in 2020. Centuria, in turn, promoted Der III Weg’s endorsement of the organization.

Centuria emphasizes the importance of providing Ukrainian youth with nationalist education. “No government in Ukraine has been interested in educating the youth,” reads a blurb on Centuria’s official website. “They thought only about their own enrichment, not about building the national future. Our task is to raise a strong, proud Ukrainian.” Centuria often announces efforts to recruit boys as young as 15 years old.

Marko* is one such youth, recruited into Centuria as a teenager. He speaks about Centuria with the formality of a spokesperson. “We consider right-wing, patriotic movements very important to our country,” he said. “Centuria was formed for the Ukrainians who want to see Ukraine be a strong, independent, and prosperous European state.

“We believe that the best ideology for Ukraine is nationalism. Our nation, language, traditions and customs have been destroyed by enemies for much of history, and now, the Russian invaders are again trying to wipe the Ukrainian nation off the face of the earth. We will never forget how Russia tried to destroy our nation, and we will take revenge for every drop of Ukrainian blood shed.”

Marko poses in front of a Nazi Party flag hanging on the walls of his barracks. “That’s just to troll the Russians,” he said. “Because the Russians are always calling us Nazis. The Russians are the real Nazis.”

But Marko’s Instagram account contains enough virulently racist, misogynistic, and homophobic rants to fill a manifesto. He quotes George Lincoln Rockwell, the founder of the American Nazi Party. “If Israel is a Jewish Country and has the right to be Jewish, if Ghana is a negro country and has the right to be black, then why don’t we whites have the right to keep our white race?” He decries the white women who have children with “Chinese, Turks, Arabs, and Negroes”, wears a shirt that says, “White Pride World Wide”, and complains that Ukrainian youth aren’t sufficiently educated about Ukrainian nationalism.

Oleksander*, 24, is another Centuria member who joined an Azov unit when the war began. His Instagram is full of masked selfies in uniform, sometimes featuring a Hitler salute. Oleksander quotes figures he finds inspirational, like Adolf Hitler and American neo-Nazi Dylann Roof, who shot and killed 9 people in a predominantly Black South Carolina church in 2015.

“Once I found out who Dylann Roof was, I read his manifesto,” Oleksander said. “I began to admire him. I understand him, because he is a nationalist, like me. I support him. He is a man who loves his nation. The blacks commit crimes against his nation, and those crimes go unpunished. He is a hero. My call sign in my military unit is his name.”

Oleksander bristled when asked if he considered himself a neo-Nazi. “Ukrainian nationalists and Nazis are two different things,” he said. He didn’t respond when asked why he’d quote Adolf Hitler if he didn’t have Nazi sympathies.

Anton Radko, 32, is a professional MMA fighter and trainer who became an Azov commander after the war started in Ukraine. He, too, complains when he is referred to as a neo-Nazi, though he, too, uses Nazi iconography and white supremacist symbols liberally.

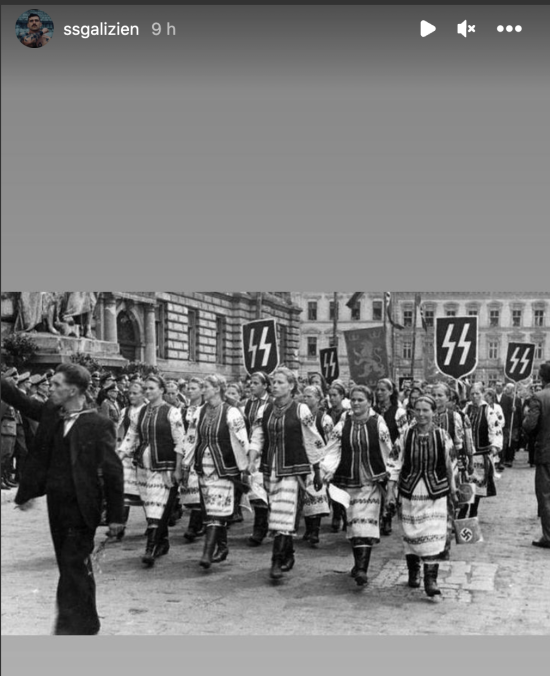

The username of Radko’s private Instagram account was “SSGalizien”, referring to the predominantly Ukrainian 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the Nazi SS. And fittingly, Radko posted Nazi content, including pictures of Nazi party flags and SS marches, on a near-daily basis before his account was suspended by Instagram. The Azov Regiment, which has claimed repeatedly to have purged its ranks of neo-Nazis, uses Radko in its official videos, social media posts, and even on billboards in Ukraine.

Groups like Azov have long been a draw for far-right volunteers from Western countries. It’s not clear how many foreign volunteers have traveled to Ukraine to join Azov, or how many have switched from other militant groups while in Ukraine. Centuria’s Poltava division recently shared an interview with a 23 year-old American militant in their ranks. “Francis,” from Texas, came to Ukraine and joined the International Legion, the official unit of foreign volunteers.

“I always wanted to join Azov,” Francis said. “I jumped when I got the chance.” When asked about how he felt about the US government’s issues with Azov, Francis said he was unconcerned. “To be honest, I don’t care,” he said. “I have my own opinion. I came to work, help, and support my friends.”

Azov and the West

US Congress has included stipulations in appropriation provisions that Azov may not receive “arms, training, or other assistance.” But a 2021 report found that that Azov Centuria members were trained by Western countries while at the Hetman Petro Sahaidachny National Army Academy. But it’s clear that US aid is reaching Azov. Azov militants are frequently seen in photos with weapons provided to Ukraine by Western countries.

Beyond aid from Western governments, private donations have poured into Ukraine from the West. In March, money transfer and online payment system PayPal expanded their services to allow Ukrainians to receive funds from abroad. Virtually every Azov militant with social media uses it to court donations.

One Azov militant sought donations in honor of a fallen solder in an English-language Instagram post. “He spoke about support of the European people against Black Lives Matter riots. Our fight is 14 words,” referring to a quote from American neo-Nazi David Lane: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White children.” The Azov militant linked his PayPal account at the end of the post.

In September, a delegation of Azov members visited Washington, reportedly meeting with more than 50 members of Congress. The meetings apparently went so well that an Azov co-founder present in them, Giorgi Kuparashvili, predicted that Congress would remove the ban on funding and arming Azov.

The current size of the Azov Regiment is unknown, though the size of Azov relative to the Ukrainian Armed Forces as a whole is often cited to downplay the influence and danger of the organization. As a result of a widespread, continuous recruitment initiative, Azov’s ranks are growing. Azov’s recruitment page mentions that special dispensations can be made for active military personnel who aren’t able to visit recruitment centers in person, indicating that Azov is potentially swelling its ranks by poaching soldiers from elsewhere in the Ukrainian Armed Forces.

Azov is one of a number of ultranationalist militant groups active in Ukraine. Although bans on US funds being used to arm and train militants only apply to Azov, the rest of the Ukrainian far-right is equally problematic.

Ukraine’s Far-Right Beyond Azov

Carpathian Sich, a volunteer battalion formed by the ultranationalist Svoboda Party in 2014, was originally comprised of nationalists unable to enlist with the National Guard. Carpathian Sich’s current iteration, the 49th Separate Rifle Battalion of the Armed Forces of Ukraine, has been an official part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces since May and has a substantial number of foreign volunteers. Unlike Azov, Carpathian Sich seems to have muted its overt expressions of neo-Nazi ideology since the war began.

While volunteers from the US and Europe were welcomed into Carpathian Sich, a volunteer from a South American country says volunteers from his part of the world had a different experience. The volunteer, an army veteran, visited a Ukrainian Embassy and was encouraged to travel to Ukraine to join the International Legion. Once he arrived, the International Legion rejected him because he didn’t speak English. He was directed to Carpathian Sich.

The volunteer says that Carpathian Sich initially refused to enlist volunteers from South America. Eventually, they agreed to spend a month on the frontlines without payment. At the end of the month, Carpathian Sich was satisfied with their performance and enlisted them. The South American volunteer said he planned to remain in Ukraine permanently after the war.

Mikhail*, a militant from a Carpathian Sich-linked militia, says non-white volunteers should go back to their home countries as soon as the war is over. “Europe is white,” he said. “Europeans are meant to be white. This is how we Europeans differ from savages such as the Russians.

“We appreciate the help people from other countries have given us,” Mikhail continued. “But we have paid them, and they really should go back to their countries when the war ends. This is why we send food and grain to Africa, for example. So they don’t flee to Europe and try to live here.”

Right Sector

The Ukrainian Volunteer Corps (DUK) is the militant wing of the Right Sector, a far-right wing, ultranationalist organization founded in 2013. Today, the DUK is an official part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. But in the years following the Euromaidan, even as other militias split or merged into the Ukrainian Armed Forces, Right Sector remained independent. Though Right Sector’s prolonged consternation with Ukrainian authorities eventually mellowed, the organization’s ultranationalist, neo-Nazi ideology remained strong.

Right Sector rails against the LGBT community and feminism, even crediting the war in Ukraine for slowing the spread of tolerance by causing the departure of “most supporters of feminism and LGBT”. Human rights watchdog organizations have cited Right Sector’s role in many violent, racist attacks, noted that some municipalities have used members of far-right groups as street police, and complained that Ukrainian authorities have prosecuted activists attacked by far-right groups while taking no action against their far-right attackers.

Right Sector has an active youth outreach program with chapters throughout the country. Like Centuria, Right Sector places heavy emphasis on nationalist indoctrination of youth. “Right Sector seeks to educate the youth and eliminate the internal occupation,” said one DUK militant whose Instagram username features both “white boy” and “88” (a numeric abbreviation for “Heil Hitler”). “That means the political forces that reduce the rights of our indigenous nation to a minimum.”

As with Azov and all other far-right militant groups in Ukraine, the current size of the DUK is unknown. The DUK consists of “combat units, reserve units, operational units, initiative groups for the creation of reserve units, training centers, local training bases, and other auxiliary structures.” New militants are actively being recruited. As with Azov, Right Sector mentions that it’s possible for soldiers in the Ukrainian Army and elsewhere to transfer into DUK.

The Other Carpathian Sich

“Alien, remember! The Ukrainian is the boss!” chanted black-clad men demonstrating against the Hungarian minority in Uzhgorod in 2017. The demonstrators were members of a second, distinct group named Carpathian Sich.

This Carpathian Sich existed pre-Euromaidan and has been responsible for many of the worst attacks against marginalized communities in Ukraine. Among the group’s stated activities are patrols to combat “ethnic crime.” Carpathian Sich often joins forces with Azov and Right Sector. In 2016, 300 members of the three groups marched through the streets of Uzhgorod, calling for the extermination of Hungarians.

Carpathian Sich founder Teras Deyak says that at the start of the war in February, Carpathian Sich reformatted into a military unit. Existing members took up arms, and volunteers approached Deyak to join. In the years before the war, Deyak actively participated in Carpathian Sich’s attacks on feminist demonstrations. In 2017, Deyak filmed attacking people inside a bar in Uzhgorod and yelling “Sieg Heil!”

New Far-Right Groups Emerge

As the war drags on, there is an ever-growing number of new far-right militias appearing in Ukraine. Ilya*, a Russian militant belonging to the Russian Volunteer Corps, a new unit of far-right Russians fighting against Russia in Ukraine, has a tattoo on his left hand bearing an SS logo and the numbers 14 (“14 words”) and 88. In one of the photos on his Instagram, he is standing in front of an American flag. 14, 88, and SS are written on his ear protection.

Still, Ilya balked at being labeled a neo-Nazi based on his use of neo-Nazi insignia. “1488 is a lifestyle,” he said. “Muslims kill people all the time, but no one is trying to cancel the Islamic religion. And the world is determined to commit genocide against white Slavs, so this lifestyle is necessary,” apparently referencing the inherently white supremacist “Great Replacement” theory.

There’s Nordstorm, co-founded by an Azov Centuria militant from Latvia. “Nordstorm is more radical than Centuria. “We are engaged in more right-wing, radical actions,” he said in an interview. “The things we do are illegal, and I can’t say what they are. But the people who know Nordstorm know what we do very well.”

Additionally, white supremacists are plentiful within militant groups in Ukraine that aren’t inherently far right, like the Kastuś Kalinoŭski Regiment, a unit of Belarusian volunteers. One Belarusian volunteer with the Kastuś Kalinoŭski posted collection of horrifically racist poetry on his Instagram account. Excerpted from one: “Once in the white Europe, enslaved by the Jew. They broke in like their own home. Open doors cannot be closed.”

In short, Ukraine’s far-right is a growing problem, and it’s much bigger than the Azov Regiment alone.

“Here comes the myth that we’re Nazis,” said Boris* an Azov militant and member of Misanthropic Division, frustrated by our questions about the use of white supremacist symbols. “Russians confuse nationalism and Nazism.” We asked why so many nationalists in Ukraine would get Swastika tattoos, express admiration for the SS, and use 1488 if they weren’t neo-Nazis.

“We’re just trolling the Russians,” he said.

* an alias.

** the Totenkopf in this style is a Nazi Symbol. The patch reads “Boys of the Northern Capital”, which is an openly neo-Nazi football club.