On September 11, 2020, two Kurdish farmers, Servet Turgut and Osman Şiban, were thrown from a Turkish military helicopter in the southeastern province of Van, Turkey. Turgut died from his injuries on September 30th, and Turkish authorities implausibly claimed that he’d fallen from a high rock formation while trying to escape arrest by the Turkish Jandarma.

Journalists from the Mezopotamya Ajansi obtained the victims’ medical reports, witness statements, and visited the site of their abduction. There were no high rocks in the area, only pastureland for livestock. Villagers who witnessed the abduction said that Turgut and Şiban were uninjured when they were detained and forced into the Turkish military helicopter.

Osman Şiban was released from the hospital on September 20th. He hasn’t fully recovered from his injuries and suffers severe memory loss. Despite that, on January 2021, he was again arrested by Turkish security forces, and accused of aiding and abetting a terrorist organization. The criminal case against him is ongoing.

To date, the only other individuals who have been arrested in relation to the crime of throwing two men from a military helicopter are the journalists who dared to report on the incident. Cemil Uğur and Adnan Bilen of Mezopotamya Ajansi, Şehirban Abi of Jin News, and freelance journalist Nazan Sala were arrested on October 6, 2020. “The house where I live in the center of Van was raided and searched by police,” Cemil Uğur said. “Later, I was taken out of the house and taken to the counterterrorism branch of the Turkish police.”

Uğur says he and his colleagues were barred from seeing an attorney for the first 24 hours of their detention and were prevented from showering for four days. After an initial court appearance, they were taken to a high security prison in Van. They spent 45 days in a quarantine ward before being moved to the general population. They ultimately spent six months behind bars before being released to await trial.

Since the July 15, 2016 coup attempt, hundreds of journalists have been arrested in Turkey. The Turkish government vehemently denies this, claiming that the journalists arrested are members of terrorist organizations. “Since the arrest of journalists is not welcome in the world, the Turkish government claims it doesn’t arrests journalists for performing journalism,” said Hüseyin Aykol, veteran journalist and writer for Yeni Yaşam. “To ensure that they’re sentenced to many years in prison, they’re charged with membership in terrorist organizations. Sometimes, they’re even charged as leaders of terrorist organizations.”

Aykol started his journalism career as editor-in-chief of “Socialism: Theory and Practice,” a magazine published in more than 20 countries. He was first arrested for his journalistic work in 1981. He was charged with membership in a communist political party and spent more than 10 years in prison.

After his release, Aykol began working for news outlets affiliated with Özgür Basin Gelenegi (Free Press Tradition). Since 1990, he has been the director of more than 50 weekly or daily newspapers. The volume is so great because most of these outlets are officially shuttered by the Turkish government after a period of months, at which time they regroup and re-emerge with a new name and a new office location. “When each of our newspapers was closed by a court decision, we published a new newspaper with another team, with the same understanding, and continued on our way,” Aykol said. “Some of our newspapers were very lucky and lasted more than a year.”

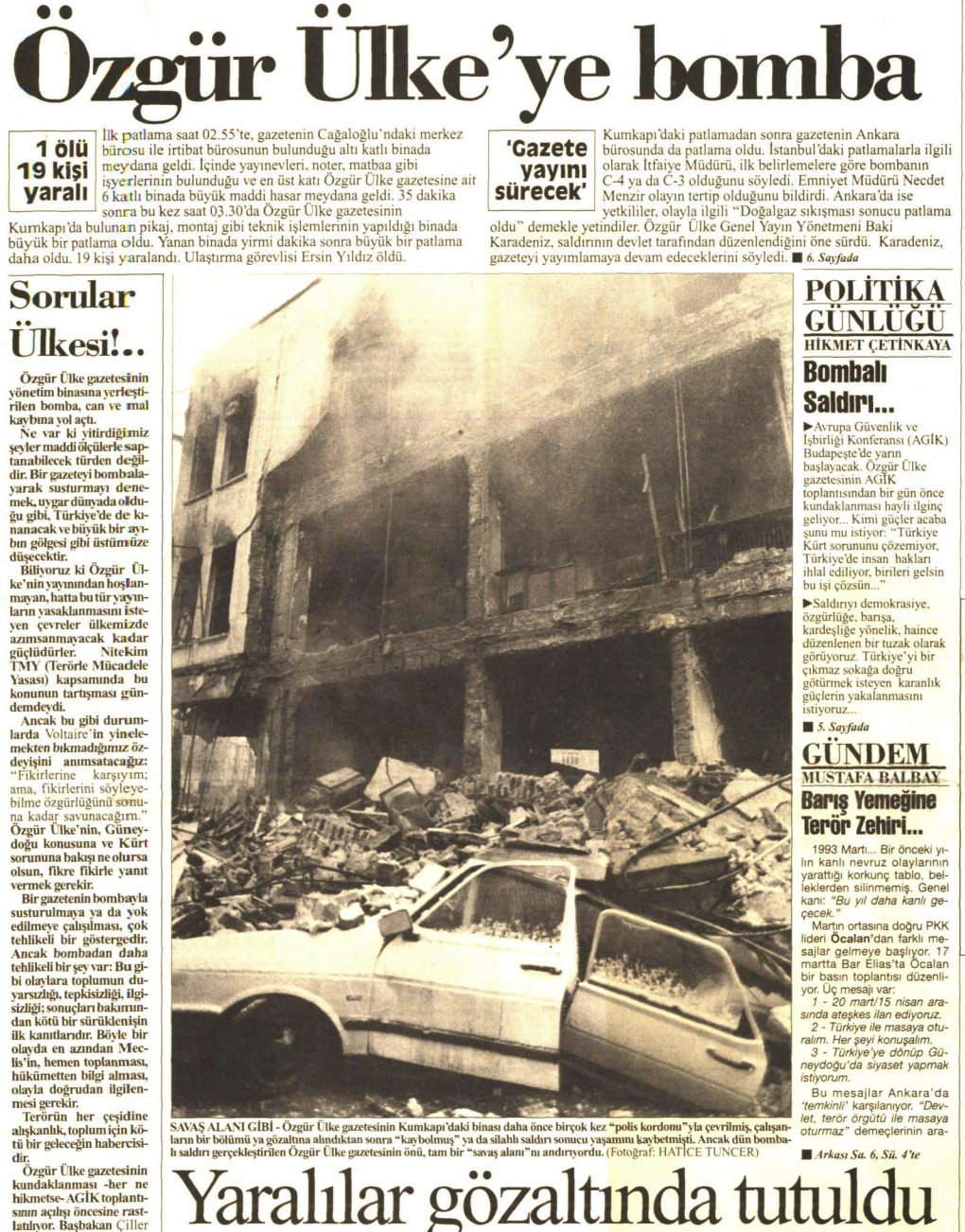

Interference from the Turkish government is one of many obstacles critical journalists in Turkey have faced. Aykol and his colleagues have endured decades of targeted attacks, including office bombings and assassinations. On December 3, 1994, three offices of newspaper Özgür Ülke were bombed simultaneously. One journalist, Ersin Yıldız, was killed when the blast forced the second floor newsroom to collapse onto the first floor entrance. 23 others were injured.

“There was a police station 50 or 60 meters away from the office, and when they heard the bombing, they rushed to the scene and detained anyone who happened to leave the building,” Hüseyin Aykol said. “For them to question the journalists who were in the building is normal procedure. But these should have been taken as victim statements. Instead, they created the perception that we had bombed our own newspaper.” Ultimately, no one was charged in the bombings. Aykol and many others believe former Turkish Prime Minister Tansu Çiller was behind the attack.

The Turkish government has 63 open cases against Aykol. He was arrested in July 11, 2019 and held in prison for four months due to a ruling in one case. He is awaiting Supreme Court review of six of his open cases. “If any of them are upheld, I will have to go back to prison,” Aykol said. “If all the sentences given in my cases are approved, I will have to stay in prison another 20 years.”

Now, Aykol is a mentor to the journalists of Mezopotamya Ajansi. And as in previous generations, many of these young journalists have been arrested and criminally charged by the Turkish state. “I feel sorry for my young friends even when they are briefly detained,” Aykol said. “But when I hire them, I tell them openly that this can happen to them. I tell them that journalism is a way of life, and that we are soldiers who take part in the struggle for democracy in our country. I tell them they have come to a difficult, but honorable profession. I always try to be on their side when they are on trial, especially when they are imprisoned. Not leaving them without a letter or book in prison is one of the things I care about the most.”

Cemil Uğur said he wasn’t afraid when he was arrested for reporting on the Van incident last year. “I’m used to it. This was the second time I’ve been arrested. I knew reporting on the two civilians thrown from a military helicopter would lead to my arrest, and so did the other journalists reporting on it.”

Currently, 20 Mezopotaymya-affiliated journalists are in prison. At least 160, including Cemil Uğur and Adnan Bilen, are awaiting trial. Uğur, Bilen, and three of their colleagues last appeared in court for charges related to their Van reporting on July 2nd. Their case was postponed.

“They arrested us to avoid people hearing facts the government didn’t want them to hear,” Uğur said. “There is something they’ve forgotten; in history, many governments arrested journalists who brought the truth to the public. But these governments never succeeded in drowning out the truth.”